Returning your horse to a more normal weight is essential for long term health and happiness! Arriving at a normal body composition, at it’s simplest, is the combination of calories consumed and calories expended. If your horse needs to lose a couple (or more) pounds, he will need to use more than he eats.

EIA (Coggin’s) Test

What is a Coggin’s test, and why do I need to get one for my horse?

New horse owners ask about Coggin’s testing frequently, and not having one when you need it is a real headache. The test checks for antibodies to a particular virus, the Equine Infectious Anemia (EIA) virus. It is named for it’s inventor, Dr. Leroy Coggins. The test is regulated by the federal government, can only be drawn by a licensed and accredited veterinarian, and must be run in a federally accredited laboratory.

There are several important reasons to get an EIA test on your horse.

- Interstate Travel. Most states require a negative EIA test within 12 months of entry to their state. Usually a Certificate of Veterinary Inspection (a “Health Certificate”) is also required, and additional requirements vary from state to state. We have current information on travel to all states as well as foreign countries.

- Purchase of a new horse. Our recommendation is that you get a new EIA test run when you buy a new horse, prior to concluding the purchase. The federal government has specific regulations for managing positive horses, none of which you want to be involved with. In addition, all infected horses eventually die from the virus, which likely makes the purchase a poor decision.

- For Medical Diagnosis. Horses that are depressed, anemic, running a fever that doesn’t resolve, or have other specific signs suggestive of EIA infection will have an EIA test run for diagnostic purposes.

Where do you run the EIA test, and how long does it take?

Our laboratory is federally accredited to run EIA tests, and has been for a number of years. It is the only local laboratory in Elbert County. We routinely run the tests several days a week, and results usually take only a few days. In cases of an emergency (“I forgot that I needed a new one and I’m leaving this afternoon is the usual emergency!”) we can get while you wait results for you at an additional expense.

This is what an EIA test report looks like.

Our lab uses Globalvetlink for reporting. The report comes to you via email as a PDF which you can open and print whenever you like.

Call or email to make an appointment!

303-841-6006 office

office@cherrycreekequine.com

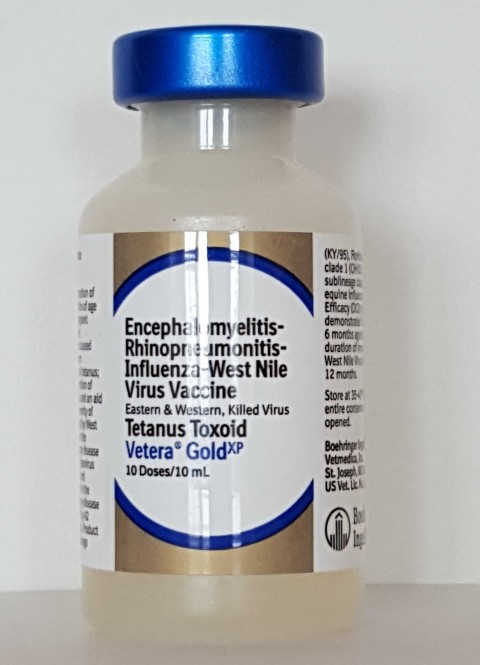

Spring Vaccinations keep your horse healthy!

Spring vaccinations are an important part of keeping your horse healthy. The routine spring vaccine includes protection for:

- Eastern and Western Equine Encephalomyelitis (also called “Sleeping Sickness”)

- Influenza (“Flu”)

- Rhinopneumonitis (also called “Equine Herpes”, EHV)

- Tetanus

- West Nile Virus

- Rabies

These are diseases that are commonly encountered in horses. Here in Colorado, the highest risks of exposure are for West Nile virus and Rabies, as well as the respiratory viruses. We immunize for these in the spring because the encephalitis and West Nile viruses are spread via mosquito bites. Protection persists through the entire mosquito season. If your horse travels to the deep south or the coasts, a second encephalitis booster is recommended in the fall to provide year round protection for these diseases. Rabies vaccine should be boosted once yearly in the horse.

Laminitis (Founder)

“My horse has foundered, what does that mean?” Laminitis (founder) is a lameness condition that is characterized by the loss of the normal attachment of the hoof to the coffin bone. There are a variety of causes for this disease including an episode of overeating in the grain room, hormonal causes, and as an after effect of high temperature or severe infection. Rarely it can be caused by damaged circulation from a wound or other loss of circulation. When the attachment of the hoof to the bone is damaged, the loss of attachment is usually most severe at the front of the hoof, which results in the most tearing at that point. On a radiograph from the side of the foot, it appears that the tip of the coffin bone has rotated downward, creating the classic x-ray image of a foundered foot. Traditionally, severity has been assessed by the number of degrees of difference between the front of the coffin bone and the hoof wall, termed degrees of rotation. The more rotation, the worse the laminitis episode is thought to be, and the less likely the horse will return to normal. Occasionally, the damage to the attachment is so severe that the entire hoof becomes detached from the bone, leading to the bone dropping straight downward with no rotation. These are termed “sinkers”, and the prognosis is much less favorable than a horse with a less severe amount of rotation.

Laminitis can be difficult to prevent. There are a number of metabolic events that occur when a horse develops laminitis. In some instances, like the grain overload situation, the horse consumes a large amount of grain and as it passes through his digestive system, the grains ferment, and toxins called endotoxins are released. These toxins alter blood flow to the foot, cause damage to the lining of the blood vessel in the laminae, and in that way damage the hoof attachment. Laminitis can also occur after a colic episode, and the endotoxin release from the GI disturbance is thought to have a similar effect. There are a number of stress related that are involved as well, with cortisone one of the most important. Horses that have a cresty neck and are obese are at increased risk for laminitis because of a direct adverse effect of insulin on the laminae. Horses with Equine Metabolic Syndrome have significantly elevated insulin levels continuously, and the effect of increased cortisone in the blood stream makes the insulin level climb higher. Eventually, a critical level is reached, the laminae are damaged, and a laminitis episode ensues. Horses that have PPID (Equine Cushings Disease) have persistently elevated cortisone levels in their bloodstream, which causes insulin resistance as well. Treatment of these conditions involve weight management, dietary changes, and medication to control the PPID if it is present.

About Mud and Horse Feet…

It’s only April, and both the horses and the vets are already tired of the mud. Muddy pens means wet feet, and all of the problems that go with them. In the past couple of weeks, we’ve seen a huge increase in the number of hoof abscesses, thrush, and skin infections on pasterns and heels, all because of the muddy (and other stuff) pens the horses stand in all day.

Just like when you soak in the bathtub for too long and your feet get all wrinkly, the horse’s foot softens when standing in wet environments, making it more permeable to barnyard bacteria and contaminants. If your paddocks or pastures have gotten muddy and wet with all of this snow melt, it’s really important to clean out your horse’s feet, wash off the caked-on mud, and give your horse a dry place to stand for a while. It’s a lot easier than treating problems…

My horse has a cut… what should I do?

“My horse has a cut on his leg, what should I do?” This is one of the most common questions we hear. The critical things to know are depth, discharge, and whether important structures are involved. Wound depth can not always be determined by looking. In a typical wound, you can see hair missing, a raw spot, and maybe edges and deeper structures. If all you see is missing hair, the wound is not serious, and all that is required is to keep it clean with water. If you are able to identify complete edges on both sides of a wound, the wound is termed full thickness. Full thickness means that the skin has been cut clear through, and that structures inside are exposed to the outside. These wounds require inspection by your veterinarian, because they often are like an iceberg, bigger on the inside than on the outside. There may be tendons, ligaments, muscles or joints underneath that are damaged, and often there is debris like manure and hair packed inside. These wounds are likely to get infected and need medical management in order to get good healing. The last bit of information to process is whether or not important internal structures are involved. Wounds that involve joints, tendon sheaths, tendons, ligaments, or bone are particularly serious because infection or injury to these structures can become life threatening. These wounds can often be managed successfully if diagnosed early. Once infection has set in, it is much more difficult to achieve a good outcome. An important part of this assessment is determining how much pain the horse is in. If he is limping or unwilling to bear weight, is off feed or lethargic, it’s time to call your veterinarian.

A similar question is whether or not a wound needs stitches. Wound suturing is recommended for larger wounds, wounds with a lot of injury underneath the skin, if tendons, muscles, or joints are involved, and if a good cosmetic result is desired. Usually, sutured wounds heal faster than those left to heal by themselves, with less scarring. Wounds over joints can be successfully sutured, they just require specialized bandaging to limit movement while the cut heals.

“My horse’s wound has pus coming out of it. What should I do?” These wounds are infected, usually with bacteria and debris from the skin, as well as the barnyard. Infected wounds are swollen, red, have discharge, may or may not smell bad, and are painful. These wounds are treated in two ways. First, it is essential to decontaminate the wound. This is done by applying large quantities of hypertonic saline solution to the wound to dilute the discharge. In a pinch, you can use a garden hose to decontaminate a wound. Do not apply Furacin, disinfectants, antibiotics, soap, bleach, Vetricyn, or other substances unless directed to do so by your veterinarian. Sampling of the wound for bacterial culture and determination of antibiotic sensitivity may be very important in order to get the infection resolved. Bandaging of draining wounds on legs is helpful to remove discharge and protect the raw surfaces from recontamination by the environment. The frequency of bandage change is determined by how quickly drainage soils the bandage material. It is very possible to suture wounds that have become infected once the infection is under control, using a technique called delayed primary closure.

Pain management for horses with wounds is very important. Numerous studies have shown that adequate pain management speeds and improves the quality of wound healing. It is a matter of humane treatment of animals as well. Minor wound pain is often well managed with anti-inflammatories like phenylbutazone, Previcox, or others. More substantial wounds may require opiates, local anesthetics, epidural, or other modalities to adequately control the pain.